Today I finally got around to finishing my first design for a switching LED display backlight driver. The circuit is built around a LT3518 switch mode driver IC working in buck (step down) mode in this application.

Someone figure out why SMD hand-soldering always looks ugly on macro images…but trust me on this, the circuit works like a charm ;-) The flux residues don’t hurt performance, but you really do want to keep any solder-balls or whatever metalliccy is floating around your circuit away from the tight parts. If necessary, rinsing it with alcohol while carefully assisting with a brush does the job, followed by a soft coating of plastic spray to prolong the circuit’s life.

My design was done rather quick and dirty because it needed to get done. Just don’t expect THE most absolutely high frequency capable layout, though I guess that prominent airwire in the first picture crashes this illusion anyways. Consider this more of a first prototype to check out what this chip has up its sleeve in buck mode after already trying boost mode on Tobi’s LED driver, which will also be documented later on. So far, it seems to keep up with my demands quite well, it will be modified and optimized later on.

Measurements (all taken at maximum brightness with a tRMS multimeter):

| V in | I in | V out | I out | P in | P out | Efficiency | |

| Mains | 20 V | 0.25 A | 9.6 V | 0.400 A | 5.0 W | 3.84 W | 77 % |

| Battery | 11 V | 0.41 A | 9.6 V | 0.400 A | 4.51 W | 3.84 W | 85 % |

Higher efficiency on battery is just perfect, even though it is barely into the operating voltage range. The measurements made on the go, so the numbers might not be absolutely accurate. If there is time, the scope will clear that up. Also, keep in mind that battery voltage will drop some over time. According to standard Li-Ion specs, it ranges from 12.75 V charged to 9.3 V discharged (although I have never seen it go below 10.5 V so far).

The schematic and board layout will be available in the next few days in EAGLE format, together with more photos of the “implanted” driver. Need to clean up the parts naming and stuff first.

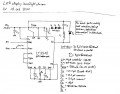

While I am on it, enjoy my wicked hand drawing skills :-D

A few things to add to the drawings: First, the schottky-diode is of SK34A type, secondly the ceramics are all of X7R-rating type (refer to datasheet of the LT on this one) and thirdly the connection between TGEN and CTRL/VREF ist also an airwire, which can clearly be seen dominating the circuit in the pictures and is unbelievably oversized.

This article will be followed by some pictures of the LED array and driver mounted inside the display. The former was already installed before I started this blog so I didn’t think of taking some shots at the time. It is nothing spectacular really, some chip-on-board (COB) slimline LED modules bought over at led-tech.de, soldered together and cut to correct length, then glued into place instead of the CCFL with thermal conductive glue.

NOTE: While testing the device to its limits, I am experiencing some problems at very low system voltage. When on battery only, the notebook’s internal supply lines drop to around 10 to 12 volts as opposed to rock-solid 20V when the mains is connected.

This driver was designed with up to 20V and only down to about 12V input in mind, which means a maximum of 80% switching duty cycle at low voltage. I figured that the internal supply lines would be thoroughly regulated but was mistaken as it seems. As soon as the voltage drops a quantum too far while powered only by batteries (eg. more power is drawn by any device), duty cycle rises over some magic number around 96% at 250kHz (see data sheet) and flickering occurs as the IC loses control over the current. This is why there certainly will be a v2 of this, and it will be buck-boost-mode to handle low voltage situations even better. I might also want to fix minor problems with shutdown mode still allowing a very small current through the ICs internal switch, but in comparison this one is totally unimportant.

Right now the v1 driver is successfully implanted in the screen bezel and works nicely. Screen brightness even beats the original CCFL backlight, though the lower screen border is not absolutely uniformly lit. I could care less, thanks to the windows taskbar using up that space. The notebook is a SX65S by the way.